Intractable Problems in Present-Day Soccer Analytics

Published on October 26, 2023

The New York Times recently published a profile (their second one!) of Ian Graham, the former Director of Research at Liverpool FC and all-around soccer data powerhouse. It is primarily focused on his new advisory business but contains some interesting tidbits that, at the very least, offer something fun to think about:

‘In that time, it might allow [Graham] to attain what he regards as the “holy grail” of analytics: assessing the actual significance of a manager. “That’s very complicated”, he said. “It tends to be conflated with who has the best players, the best team. There are a lot of second-order effects. It’s very hard to know exactly how good any manager is, and what sort of impact they have on results.’ (Emphasis added.)

Those new to the world of soccer analytics might react to that statement with surprise, but precisely measuring how good any manager is in any standardized way is a very intractable problem, and this makes those managerial hiring decisions (like most others) a slightly more complicated endeavor than people generally realize.

Why? Well, Graham sort of gives away the reasons in that quote, but for a more detailed explanation, let’s start at the top.

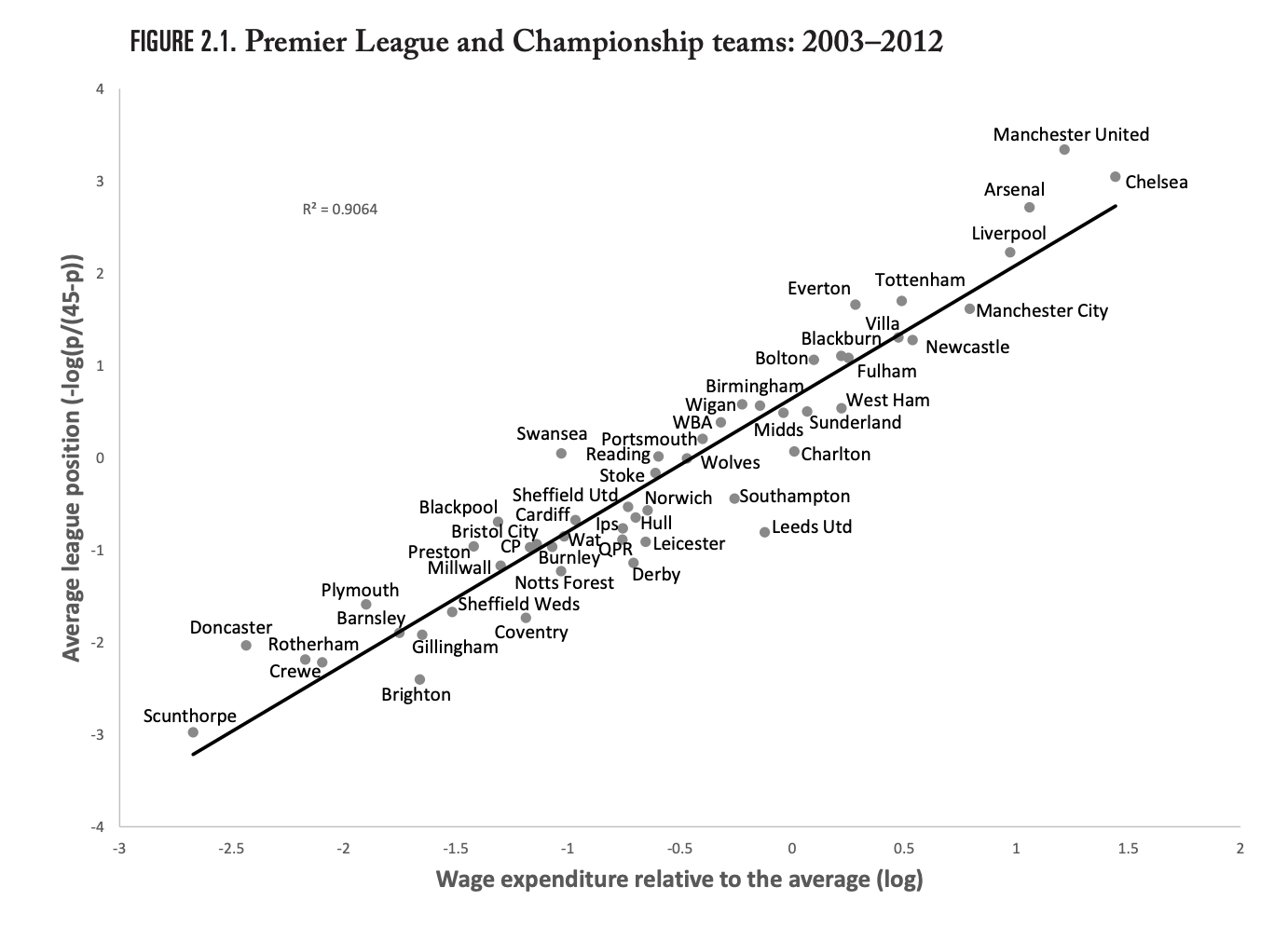

One of the most tried, tested, and replicated findings in the study of soccer/soccer economics/soccer analytics is that player wages correlate very positively with performance. Simply put, the wages clubs paid their players was the single best predictor of their average finishing league position over long periods, and it explains somewhere between 70 – 90% of clubs’ revealed differences in performance. The best teams have the best players who receive the highest wages – which are paid by the best teams, more or less. This was popularized initially by Simon Kuper and Stefan Szymanski’s ‘Soccernomics’, the first version of which was, among other things, the first soccer analytics book I read. (Chart from book.)

The most prominent effect of this correlation was it helped create a generalizable framework for evaluating the impact of managers on teams and clubs. Actually, that’s wrong. The anecdotal understanding of this trend by sporting management has been the basis (for better or for worse) of most head coaching hires in the history of soccer, way before analytics was a thing in the first place. For instance, Manchester United hired Sir Alex Ferguson because he outperformed the trend in Scotland by breaking the Old Firm dominance. The only difference in the late 2000s was that better data meant this trend was quantifiable, meaning manager outperformance or underperformance was measurable to the T.

Of course, knowing Graham’s quote, that’s not how this story ends. Firstly, it is indeed true that we can understand some managers’ impact pretty well by quantifying wage trend overperformance. The authors of Soccernomics themselves do so in Chapter 7 of the book. However, there are flaws with this methodology that make it unusable in most practical scenarios, which poses a conundrum of sorts.

For one, the Soccernomics model assumes that the market of wages is efficient, especially over long time horizons. That probably holds. Over shorter stretches though, manager performance is impacted by different factors manifesting as, primarily, inefficiencies in the wage market, which hands them over-priced (in the case of badly-managed clubs) players or under-priced (well-managed clubs) players. As a concrete example, managers of Brentford and Brighton routinely outperform trends based on wages (and other performance measures), but how much of that is attributable to their efforts as managers vs their teams being exceptional at player recruitment is an open question. Another example from Soccernomics:

From 1991 through 2000, United’s average league position was 1.8 (i.e., somewhere between first and second place) and yet in that decade the club spent only 6.8 percent of the Premier League’s average on wages. Ferguson was getting immense bang for his buck. In part, he owed this to the Beckham generation. Beckham, the Neville brothers, Paul Scholes, Nicky Butt, and Ryan Giggs were excellent players who performed with great maturity almost as soon as they entered the first team, but given their youth they would then have been earning less than established stars.

The fundamental economic problem reads something like, “How can we allocate societies’ scarce resources to best satisfy the needs and wants of various peoples?” Every economics paper, book and sermon, in some way, attempts to answer that question on the margins. Similarly, the fundamental managerial hiring problem is “How much of our scarce resources must we allocate to player skill for this person to achieve our business objectives?” Every managerial hire, implicitly or explicitly, attempts to minimize the answer to this question.

Player wages are the closest proxy there is for the estimate of the skillfulness of any squad. The more skilled the players of a team are, the higher the wages of the team – and this is truer over the long term. Every other metric, advanced or otherwise, is a function of the skillfulness of the playing squad too. And so, like it’s impractical to estimate manager skill using wage data over the short-term, it’s impractical to use all these metrics too – while abandoning any qualitative context. Hence the Graham quote.

I found myself staring down the barrel of this very gun when I was tasked with helping a fairly large Premier League club with their managerial search. The approach I took, precisely, was:

- Assume perfect future strategy and, therefore, fit (at the hiring club).

- Find all the metrics that correspond well with success.

- Then, look for obvious signs of overperformance from the managerial candidates across all those metrics.

Of course, knowing where to look for obvious signs of overperformance requires a tremendous amount of context, qualitative and quantitative.

Imagine you’re the CEO of a team whose on-pitch performances have waned after big summer spending. You look around and compare the wages of your playing squad to others in the same league and find that your team is consistently underperforming that trend. What should you do now? Wait for it to mean revert? Sure, but you give it a couple of months and find, yet again, that nothing has changed. Should you fire the manager now? Maybe, but how certain are you that he’s to blame? Maybe the big-money summer signings were never all that good in the first place (only about 50% of ‘big’ transfers work out, so it’s very conceivable); you might have burdened your manager with overpriced signings. The point is, (even though you’ll have, in practice, reasonable estimates of underlying conditions) you’ll never know for sure because you run into the same – and, perhaps, more tedious – problems as when you need to hire managers.

If you notice, all these problems are caused by one thing: an inability to actively and independently quantify player skill and, therefore, the skillfulness of the squad. We’re forced, instead, to use somewhat messy proxies that hold great for ex-post analysis of long-term outcomes but not so much for real-time decision-making.

Now for some positivity. However limited our current options are, I’m confident that we’ll continue to find ever-better proxies for independent player skill, especially over the next few years with the release of the new joint position datasets. That should alter, in meaningful ways, the nature of soccer operations while also providing phenomenally new perspectives on the game (ask me how I know). I, for one, cannot wait.